Français

Finding Our Talk Season One

- Episode 1: Language Among the Skywalkers: Mohawk

- Episode 2: Language Immersion: Cree

- Episode 3: The Trees are Talking: Algonquin

- Episode 4: The Power of Words: Inuktitut

- Episode 5: Words Travel On Air: Attikamekw/Innu

- Episode 6: Language in the City: Ojibway/Anishinabe

- Episode 7: Getting Into Michif: Michif

- Episode 8 : Plains Talk: Saulteaux

- Episode 9: Breaking New Ground: Mi'kmaw

- Episode 10: A Silent Language: Huron/Wendat

- Episode 11: The Power of One: Innu

- Episode 12: Syllabics: Capturing Language: Cree

- Episode 13: A Remarkable Legacy: Saanich

Finding Our Talk Season Two

Finding Our Talk Season Three

Episode 10: A Silent Language - Huron / Wendat

The Huron language today survives primarily in hymns, religious texts, dictionaries and turn-of-the-century wax recordings - it is, to all extents and purposes, an extinct language. This episode looks at the historical roots of the language’s demise, present-day efforts to rekindle it in spoken form, and the cultural significance and implications of language as a ceremonial artifact.

Background

When Samuel de Champlain visited this continent in the early 1600’s, he first encountered an Amerindian confederacy of five nations and more than a dozen iroquoian-speaking tribes who collectively referred to themselves as Wendat, meaning “island people”. It wasn’t long before the French had given them a derogatory name - Huron - after their word “hure” meaning ruffian.

When Samuel de Champlain visited this continent in the early 1600’s, he first encountered an Amerindian confederacy of five nations and more than a dozen iroquoian-speaking tribes who collectively referred to themselves as Wendat, meaning “island people”. It wasn’t long before the French had given them a derogatory name - Huron - after their word “hure” meaning ruffian.

By the end of that century, this once vibrant and dynamic population of 20,000 - 30,000 had been decimated by European disease to a meager 1000 souls, and dispersed through intertribal warfare to far-flung communities in Quebec, the western Great Lakes, Ohio and Oklahoma.

Early records speak of the Wendat ( or Wyandot as it is known in the U.S.) Language as alternatively “sweet and harmonious”, and “majestic and noble”. In the 17th century, Huron/Wendat was an important “lingua franca”, the language of commerce for the fur-trade then thriving in Lower and Upper Canada.

That this language was so carefully and broadly documented did not prevent, and indeed possibly hastened, its extinguishment by the end of the 19th century. The Huron language became a “Church dialect” and lost much of its vernacular relevance, as the priests and missionaries, who were also teachers, obliged their students to learn their prayers and catechism in French. By the turn of the last century, spoken Huron had virtually ceased to exist in Québec, though Wyandot continued to be spoken in Oklahoma as late as 1970.

Part 1

Part 1

In this segment, we meet Michel Gros-Louis, a Wendat biologist, and presently a graduate student in linguistics, working single-handedly to compile a Huron dictionary and revive interest in speaking his language. We follow Michel in his various endeavors, including some informal Wendat conversation classes; a trip onto the land with his colleagues and friends where they practice the language in the context of traditional activities on the land; his work of research, compilation, editing and contacting people across North America who share his interest in Wendat.

Part 2

Part 2

In the second segment we meet individuals who have, in different ways, contributed to the preservation of Wendat culture and art, both in their traditional forms and through contemporary interpretations. François Vincent is our lead character in this segment. A member of the Wendake Band Council as cultural and historical counselor, he is also an accomplished singer and musician who has a extensive repertoire of traditional Wendat ceremonial chants as well as translated religious songs. We see him in the old chapel in Wendake.

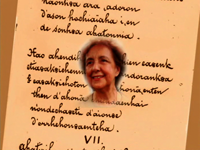

Additional characters in this segment include Mireille Sioui, a visual artist who incorporates Wendat words into her paintings, and who also has strong feelings and opinions about the role of language in cultural survival. With her, we pay a visit to her brother Christian, a medical doctor in Wendake who has also researched and published a work on Wendat genealogy. We visit him at his family home, and witness his efforts to pass on his love and knowledge of the language through the songs he writes and sings to his children.

In Montreal, we meet Sylviane Sioui-Trudel, a playwright and actress who is presenting a one-woman show drawing on Wendat history and legends and incorporating the Wendat language. She performs her play in the McCord Museum, which houses Canada’s most extensive collection of aboriginal art and artifacts and which has pioneered cultural programs in collaboration with a number of First Nations’ artists.

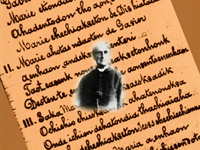

Language Keeper

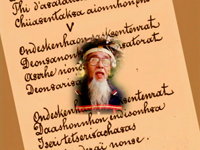

Prosper Vincent lived at the turn of the last century, a Wendat who was an ordained priest and who became a keeper and teacher of the ceremonial and translated Christian songs. He was a key source in the collecting work of Marius Barbeau and for the Museum of Civilization in Ottawa. Though he died in 1915, the legacy of his work remains in texts, songs and photographs housed at the Band Council office in Wendake, and at the Museum of Civilization in Ottawa.

Marguerite Vincent, through her extensive research, writings, and passion for her language helped culture to prosper. Frank Nataway, a spiritual leader and Mohawk linguist maintained a close relationship with many people of the Wendat Nation, sharing his knowledge and his love for the language in true Iroquoienne tradition.