Français

Finding Our Talk Season One

- Episode 1: Language Among the Skywalkers - Mohawk

- Episode 2: Language Immersion: Cree

- Episode 3: The Trees are Talking: Algonquin

- Episode 4: The Power of Words: Inuktitut

- Episode 5: Words Travel On Air: Attikamekw/Innu

- Episode 6: Language in the City: Ojibway/Anishinabe

- Episode 7: Getting Into Michif: Michif

- Episode 8 : Plains Talk: Saulteaux

- Episode 9: Breaking New Ground: Mi'kmaw

- Episode 10: A Silent Language: Huron/Wendat

- Episode 11: The Power of One: Innu

- Episode 12: Syllabics: Capturing Language: Cree

- Episode 13: A Remarkable Legacy: Saanich

Finding Our Talk Season Two

Finding Our Talk Season Three

Episode 2: Language Immersion - Cree

The history of the very successful Cree Language Immersion Program, developed and implemented in schools in the Cree communities of Northern Québec.

Background

The Cree of the James Bay region of Quebec are part of a much larger Cree nation stretching from east to west across Canada. Theirs is the most widely spoken Amerindian language in North America, involving several dialects.

The Cree were introduced to Christianity in the mid-1800's, by Anglican and Catholic missionaries, who also brought literacy through a syllabic writing system. The influx of French and English explorers, fur traders and fortune seekers, beginning a century earlier, introduced the Cree to new economic realities and possibilities.

Ironically, the impact of Christianity and of involvement in the fur trade did not seriously threaten the viability of the Cree language as they allowed the Cree to sustain the traditional way of life through which language was transmitted.

However, the 20th century brought larger scale development to the North, as the modernizing and industrializing South sought new frontiers, new resources and new ways of wielding political power and exerting control over Aboriginal populations. The Cree were inexorably pulled into its sphere of influence and quickly began to suffer a serious loss of language and culture.

Part 1

Part 1

In the first segment of this episode, we outline the modern history of the James Bay Cree, beginning with implementation of the federally-run education system and its impact on language. The first residential schools for the Cree date back to the turn of the century, following amendments to the Indian Act providing for federal control of Native education.

Children from the James Bay region were sent to primary school in Fort George (the present-day community of Chisasibi) for the first 5 years of primary school. If they pursued their education, they had no choice but to travel to distant, southern towns, among them Amos, Québec, and Sault Ste-Marie, Ontario. Along with the generally low educational standards found in residential and boarding schools went a slow erosion of the Cree language and the social, cultural and psychological damage such a system inflicted on those who were torn away from their communities and families.

In 1975, the Quebec Cree (as well as the Inuit) signed the James Bay Northern Quebec Agreement, the only treaty ever signed between First Nations groups and the Quebec government, giving them substantial control of their own political, economic and social affairs. With some of the economic tools in hand, the Cree set about reorganizing their education system, beginning with creation of the Cree School Board in 1978.

The new Cree School board was given considerable latitude through the James Bay Agreement to create curriculum based on local language and cultural interests. Though several options for incorporating Cree as the primary language of instruction were developed, a number of obstacles emerged. Most surprising among these was parents' worry that their children would become literate in Cree before English or French, thus limiting their future education and work options.

Throughout the 80's, the use of Cree in the James Bay schools remained very little different from what it had been previously: Cree was sometimes used in kindergarten; literacy in Cree was taught as a subject; and Cree was the medium of some subjects such as traditional skills, religion and physical education.

This segment relies predominantly on archival records to trace the evolution of the modern school system in Cree communities up to the early 1990's. We interview individuals who have been involved from the start and can discuss some of the difficulties and disagreements that emerged between different exponents of Cree language education.

Part 2

Part 2

In the early 1990's, a group of people in Chisasibi strongly lobbied the Cree School Board to institute a school program using Cree as the language of instruction, at least for the first few grades. In 1992, it was agreed that a pilot Cree language program would be set up in Chisasibi and Waskaganish. A curriculum was developed combining the Quebec Ministry of Education's framework, the Cree values curriculum and a language arts approach; new materials were developed, adapted or translated. Based on the success of the pilot programs, the Cree Language Immersion Program (C.L.I.P) was formally instituted in 1994.

This part of the episode was filmed in Waskaganish, where we accompany Gloria Diamond, a bright and vivacious ten-year old, and a graduate of C.L.I.P., as she negotiates the demands of her already busy life. We meet her in a classroom context, with her family, as she writes a letter in syllabics to her grandparents, and in everyday life, with her friends and playmates.

Interviews with Luci Bobbish-Salt and Daisy Bearskin-Herodier, along with footage of their participation at an upcoming Language Conference in Montreal, as we hear and accompany two of the immersion program's most passionate defenders.

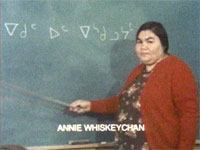

Language Keeper

Language Keeper

Annie Whiskeychan planted the seeds for the revival of the Cree language back in 1973, when she first, as a key instigator of the Cree Way Project, began teaching Cree in her primary school classes. Her efforts laid the groundwork for the later C.L.I.P. program. Through excerpts of a film made about her and testimonies of educators who were inspired by her pioneering work, we evoke the memory and life of Annie Whiskeychan.